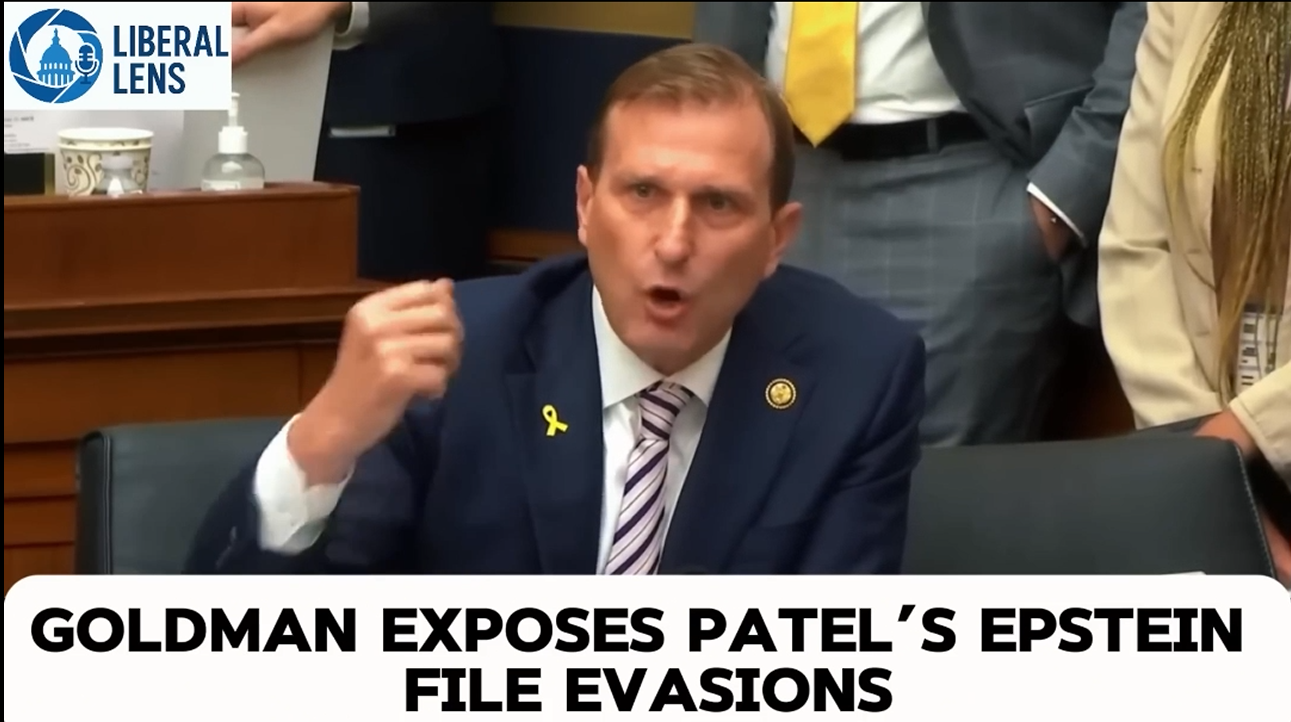

Goldman Exposes Patel’s Epstein File Evasions

WASHINGTON — A tense exchange on Capitol Hill this week between Representative Dan Goldman of New York and F.B.I. Director Kash Patel laid bare a central dilemma that has long shadowed the government’s handling of the Jeffrey Epstein investigation: how much secrecy is legally required, and how much has become a matter of choice.

At issue were the remaining investigative materials connected to Epstein’s sex-trafficking network — files that lawmakers, victims’ advocates and members of the public have repeatedly pressed the government to release, at least in redacted form. Mr. Goldman, a former federal prosecutor, used his time during a hearing to challenge what he described as the bureau’s vague and shifting explanations for why those records remain out of public view.

The exchange began with a question that was both direct and politically charged. Mr. Goldman asked whether former President Donald Trump appeared anywhere in the Epstein files. Mr. Patel responded that all names, including Mr. Trump’s, had been released where legally permissible. But that answer, meant to reassure, quickly opened a more technical debate about what the law actually prohibits.

Mr. Patel cited grand jury secrecy rules, court orders and protective orders as barriers to disclosure. Mr. Goldman accepted that grand jury testimony is protected under Rule 6(e) of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure, which strictly limits release without court approval. But he argued that many other categories of material — including search-warrant evidence and F.B.I. witness interview summaries known as “302s” — are not permanently sealed and can be revisited by judges when circumstances change.

That distinction became the fulcrum of the confrontation. Mr. Goldman pressed Mr. Patel to identify specific court orders that prevent the release of those materials and to explain why the Justice Department had not sought to have them unsealed, as it had done with certain grand jury records. Mr. Patel maintained that the bureau was releasing “everything we can legally provide,” but did not cite particular orders or timelines for further review.

The director repeatedly emphasized that the government would never release child sexual abuse material or graphic videos, a point Mr. Goldman did not dispute. Instead, the congressman narrowed his focus to evidence related to third parties — facilitators, co-conspirators and witnesses — whose identities could be disclosed with victims’ names redacted.

What made the exchange notable was not the raised voices at its conclusion, but the methodical nature of Mr. Goldman’s questioning. By separating different categories of evidence and invoking standard prosecutorial practices, he sought to show that transparency is not an all-or-nothing proposition. In federal investigations, protective orders are routinely modified, narrowed or lifted when the public interest outweighs the need for secrecy.

Mr. Patel countered that releasing such materials could still violate court restrictions and compromise victim protections. He forcefully rejected Mr. Goldman’s accusation that the bureau was engaged in a cover-up, calling it “patently and categorically false.”

Yet the hearing underscored a growing credibility problem for institutions tasked with managing high-profile cases involving powerful figures. When officials rely on broad invocations of “the law” without specifying which provisions apply — or whether those provisions have been challenged — skepticism tends to follow.

The exchange also carried a human weight beyond legal formalities. Mr. Goldman referenced Epstein’s victims, some of whom have publicly requested meetings with federal officials and clearer explanations of why certain records remain sealed. For survivors, delays and legal abstractions can feel less like protection and more like exclusion from a process that directly concerns them.

The Epstein case has long been emblematic of unequal accountability in the justice system. Epstein himself died in federal custody in 2019 before standing trial, leaving unresolved questions about the scope of his network and the extent to which influential associates escaped scrutiny. Each additional refusal to disclose records, critics argue, risks reinforcing the perception that transparency ends where power begins.

From the bureau’s perspective, caution is not optional. Law enforcement agencies operate under real legal constraints, and missteps can jeopardize cases or retraumatize victims. But oversight hearings exist precisely to test whether those constraints are being applied narrowly and in good faith.

In that sense, Mr. Goldman appeared less focused on winning an argument than on building a record — one that details what explanations were offered, what questions were left unanswered and whether future disclosures align with today’s testimony. Such records, as congressional investigators know well, often matter more over time than the headlines generated in the moment.

The confrontation offered a reminder that public trust in the justice system depends not only on outcomes, but on process. Transparency, when possible, is not merely a concession to curiosity; it is a mechanism for legitimacy. When the government declines to show its work, even for defensible reasons, it bears the burden of explaining why.

For now, the Epstein files remain largely sealed, and the debate over their release unresolved. But the hearing made one point unmistakably clear: questions about who decides what the public may know — and when — are no longer confined to the margins of the case. They are now at its center.