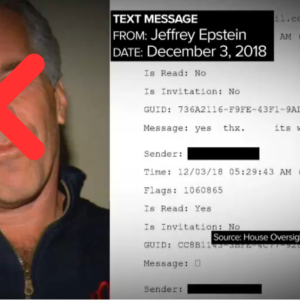

WASHINGTON — With a statutory deadline fast approaching, a dispute over the release of records connected to Jeffrey Epstein has evolved into something more consequential than a partisan clash. According to Representative Thomas Massie of Kentucky, it is now a matter of legal compliance — and potentially criminal liability.

In recent interviews, Mr. Massie has warned that if the Department of Justice fails to release materials mandated under the Epstein Files Transparency Act by the end of next week, the department would not merely be resisting congressional pressure. It would be violating federal law.

“This isn’t about contempt of Congress,” Mr. Massie said. “This is a new law with criminal implications.”

The law in question, passed by Congress and signed by the president, was designed to compel disclosure of government-held records related to Epstein’s criminal network, while allowing for limited redactions to protect victims’ identities. Unlike earlier congressional requests or subpoenas, the statute removes discretion from the Justice Department. It establishes a deadline and specifies what may — and may not — be withheld.

That distinction is central to Mr. Massie’s argument and to the growing scrutiny of how the Justice Department is responding.

In recent days, federal judges agreed to release certain grand jury materials connected to Epstein and his associate, Ghislaine Maxwell, reversing earlier decisions that had kept those records sealed. Justice Department officials have pointed to that development as evidence of progress and good faith.

Mr. Massie has acknowledged the move as encouraging. But he has also emphasized that grand jury material represents only a narrow slice of what the government possesses.

“Prosecutors don’t take everything they have to a grand jury,” he said. “They take what’s necessary to secure an indictment.”

The implication is significant. Investigators often retain interview summaries, internal memoranda, intelligence assessments and corroborating evidence that never reaches a grand jury — especially if it implicates individuals beyond those ultimately charged. Under the Transparency Act, such materials may still fall within the scope of required disclosure.

Releasing only grand jury records, Mr. Massie argues, risks creating the appearance of transparency without its substance.

The Justice Department has not publicly detailed how it intends to reconcile these obligations before the deadline. Officials have said they are balancing transparency with privacy and legal constraints, particularly with respect to victims. But critics note that redaction is a routine function of courts and federal agencies, not an insurmountable barrier.

“Protecting victims and releasing files are not mutually exclusive,” Mr. Massie said. “Names can be removed. What can’t be justified is withholding entire categories of evidence without citing the law.”

Beyond the Epstein case itself, the standoff raises broader questions about the separation of powers and the enforceability of congressional oversight. Laws compelling disclosure are often passed precisely because executive agencies have a long history of delay, narrowing interpretations or partial compliance when politically sensitive information is involved.

If an executive branch can effectively reinterpret or slow-walk a disclosure mandate, critics warn, it sets a precedent that weakens oversight well beyond this case.

“The danger isn’t just what happens here,” said one former congressional counsel familiar with transparency disputes. “It’s the signal sent to future administrations about whether statutory disclosure requirements are binding or optional.”

For survivors of Epstein’s abuse, the stakes are not abstract. Many were promised accountability and transparency after years of secrecy surrounding Epstein’s connections and the circumstances of his prosecution. Each missed deadline or partial release deepens skepticism that reputations are being protected at the expense of truth.

Mr. Massie’s framing has resonated precisely because it strips away political theater. He has not accused specific officials of malice, nor has he speculated about the contents of unreleased files. Instead, he has pointed to the law itself — its text, its deadline, and its enforcement mechanism.

“At some point,” he said, “this stops being about Epstein and becomes about whether laws designed to expose abuse of power are enforced when it’s uncomfortable to do so.”

As the deadline approaches, the Justice Department faces a narrowing set of options. Full compliance would reaffirm Congress’s authority to mandate transparency. Partial compliance could invite legal challenges and deepen public mistrust. Noncompliance, as Mr. Massie has warned, would raise a more profound question — whether the rule of law applies to institutions as firmly as it does to individuals.

What happens next will not only shape public understanding of the Epstein case. It may also determine how seriously future transparency laws are taken when they test the boundaries of power.