Epstein Photos Released as Trump Blocks Full DOJ Files

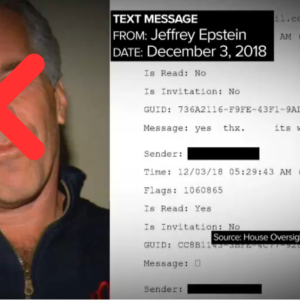

By any measure, the release of new photographs from Jeffrey Epstein’s estate was bound to attract attention. The 92 images, made public last week by Democrats on the House Oversight Committee, show Epstein in the company of some of the most powerful figures of recent decades, including former President Donald J. Trump, former President Bill Clinton, Bill Gates, Woody Allen, Larry Summers and Steve Bannon. The photographs, drawn from a trove of roughly 95,000 files recovered from Epstein’s email account and laptop, immediately reignited public fascination with the disgraced financier’s elite social network.

But the photographs, lawmakers and legal experts caution, tell only a fraction of the story. While visually arresting, they offer little insight into what investigators — and survivors — say matters most: what Epstein did, who knew about it and how the justice system responded.

The Oversight Committee’s Democratic members emphasized that the images were released only after careful review to ensure that no victims or survivors could be identified. More photographs, they said, may follow. Yet the more consequential material — emails, interview summaries, internal memoranda and other Department of Justice records — remains sealed, despite a law requiring their disclosure.

That law, known as the Epstein Files Transparency Act, compels the Justice Department to release its investigative records with narrow exceptions designed to protect victims. The deadline for compliance is approaching, but lawmakers say the department has not meaningfully responded to congressional subpoenas or provided assurances that the full files will be released on time.

Representative James Walkenshaw, a Democrat from Virginia and a member of the Oversight Committee, said the photos are “a small segment of what was received” and warned against confusing visibility with accountability. “The context for these images exists in the Department of Justice files,” he said. “Those records explain why certain documents were collected, what investigators learned and how decisions were made.”

The distinction is critical. Photographs can establish proximity — that two people were in the same room or attended the same event — but they cannot, on their own, establish knowledge, intent or criminal conduct. In court, lawyers note, images without context are among the weakest forms of evidence.

What gives the current standoff added urgency is the allegation that the Justice Department possesses far more probative material than has been released. Lawmakers say the department holds Epstein’s emails, contemporaneous notes from interviews and possibly video evidence. These records could clarify whether the photos were attachments to messages, who sent them, why they were saved and whether they were part of communications involving travel, introductions or favors.

Mr. Trump has denied any involvement in Epstein’s sex trafficking operation and dismissed the photo release as politically motivated. Still, Democrats on the committee argue that the refusal to release the full investigative record invites suspicion. “The president could release the files today,” Mr. Walkenshaw said. “The question is why he hasn’t.”

The issue has also exposed sharp partisan tensions. Republican leaders have signaled interest in compelling testimony from Bill Clinton and even Hillary Clinton, despite a lack of evidence tying her to Epstein’s activities. Democrats have called that approach a distraction, noting that congressional subpoenas have previously been defied by Republican lawmakers without consequence. To them, selective enforcement risks turning a serious investigation into a political spectacle.

Beyond Washington, the implications are broader. Transparency laws are designed to limit executive discretion by making disclosure mandatory rather than optional. When compliance is partial or delayed, legal scholars warn, it weakens the credibility of those laws and encourages future administrations to treat disclosure requirements as negotiable.

There is also a human dimension that transcends politics. Survivors of Epstein’s abuse were promised accountability after years of secrecy and failed prosecutions. For them, the release of photographs without explanation can feel less like progress than evasion. Courts routinely use redactions and anonymization to protect victims, making full transparency compatible with survivor safety.

“The public is being shown the least informative pieces,” said one former federal prosecutor familiar with large-scale investigations, “while the most important records remain locked away.”

Incomplete disclosure, experts argue, does not reduce conspiracy theories — it feeds them. Trust in institutions depends less on outcomes than on process: clear rules, consistent enforcement and explanations that withstand scrutiny.

The Epstein case has long symbolized institutional failure — not only the crimes themselves, but the decisions that allowed them to continue. The Justice Department’s files, more than any photograph, hold the answers to how those failures occurred and whether they were addressed.

Until those records are released, the story will remain unfinished. And for a public promised transparency by law, the question is no longer whether more images exist, but whether the government will fully explain what it knows — and why it has taken so long to say so.