By XAMXAM

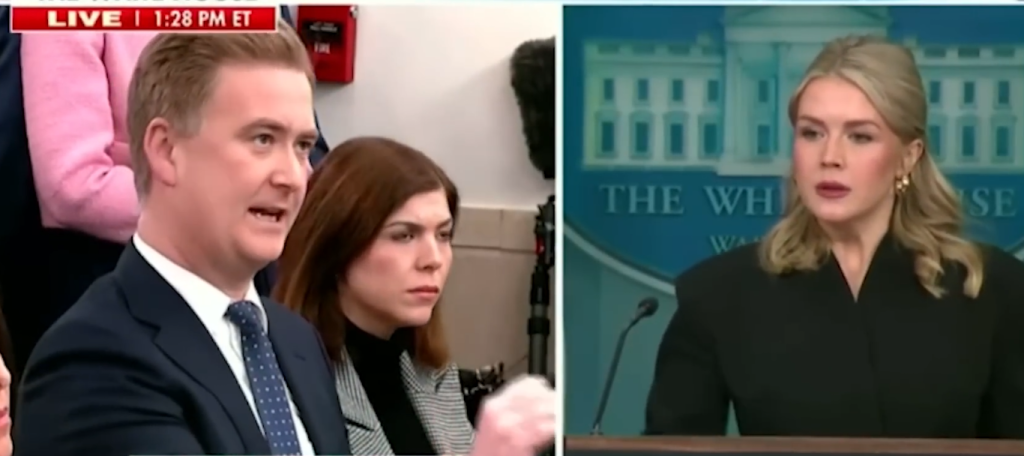

WASHINGTON — The White House press briefing is designed to be a controlled environment: a steady cadence of questions, a practiced set of answers, a ritual that turns turbulence into talking points. But the friction is the point, too. Every so often, a question lands that refuses the script — not because it is clever, but because it drags something unresolved into the fluorescent light.

That is what happened this week as the administration faced intensifying scrutiny over U.S. strikes on alleged Venezuelan drug-trafficking boats and the legality of a second strike that members of Congress described, in unusually stark terms, as “horrifying.” A situation the White House hoped to treat as a matter of operational success — interdictions, deterrence, toughness — has begun to look like something else: a test of whether the government still feels bound by the law when the targets are unpopular and far away.

The immediate controversy centers on video shown to lawmakers of a follow-up strike. According to Representative Jim Himes of Connecticut, the senior Democrat on the House Intelligence Committee, the footage appeared to show two individuals in acute distress after an initial attack — survivors in or near a disabled vessel — killed by the United States in a second strike. Himes, speaking carefully, framed the scene through the lens of the laws of armed conflict, pointing to a principle familiar to military lawyers: shipwrecked persons are generally protected from attack unless they commit hostile acts or clearly retain the capability to do so.

The phrasing mattered. “Shipwrecked” is not a poetic description; it is a category with legal consequences. Under that framework, the obligation is not to finish a target but to rescue or at least to refrain from further attack, absent clear justification. Himes’s point was not that the individuals were admirable — he repeatedly referred to them as “bad guys” — but that even bad guys can be protected by law, especially once they are incapacitated.

The administration and its defenders have argued that the survivors may have been reaching for radios or attempting to communicate with other traffickers — a rationale that aims to keep the encounter within the realm of ongoing threat. But legal experts have long warned that such arguments can be dangerously elastic. A radio can be used to coordinate harm, but radios are also the standard means by which downed pilots and shipwrecked sailors call for rescue. If the United States stretches the concept of “hostile act” to cover the mere possibility of communication, critics warn, it invites reciprocal logic against Americans.

Complicating the matter is the unresolved question of the legal framework itself. The administration has described the strikes as aggressive action against dangerous transnational organizations poisoning American communities. Critics say that absent congressional authorization or a clearly articulated armed-conflict basis, the operation resembles law enforcement conducted with military lethality — a posture that collapses the distinction between capture and kill.

That boundary is more than semantics. Law enforcement presumes arrest, due process, and prosecution. War presumes combatants, proportionality, and clear rules about who may be targeted and when. If an operation is declared “war” to justify lethal force without the constraints of policing, lawmakers want to know what limits remain — and who is deciding them.

In the middle of the debate sat another controversy: an earlier report suggesting that a “kill them all” or “no quarter” directive had been issued in connection with the boat strikes. During the briefing described by lawmakers, an admiral overseeing aspects of the operation reportedly denied that any such order was given. That denial may narrow one lane of outrage, but it does not resolve the larger one: even without an explicit extermination order, a second strike on incapacitated survivors can still be unlawful, depending on context and capability.

The political stakes are rising because the video itself is becoming the issue. Democrats and some Republicans have pushed for the administration to release the footage publicly, arguing that the country cannot evaluate what it cannot see. Administration spokespeople have suggested they are willing to release what exists, implying confidence that the context will validate the decision-making. Yet members of Congress who have watched the feed are describing it in terms that suggest the opposite: that once the public sees it, the argument will shift from policy to morality.