By XAMXAM

WASHINGTON — A tense exchange in a Senate hearing this week, sparked by Senator Elizabeth Warren’s interrogation of a senior Defense Department lawyer, offered more than a procedural dispute over legal advice inside the military. It exposed a widening struggle over who ultimately controls the boundaries of military action: elected lawmakers, civilian defense officials, or the legal professionals embedded within the chain of command.

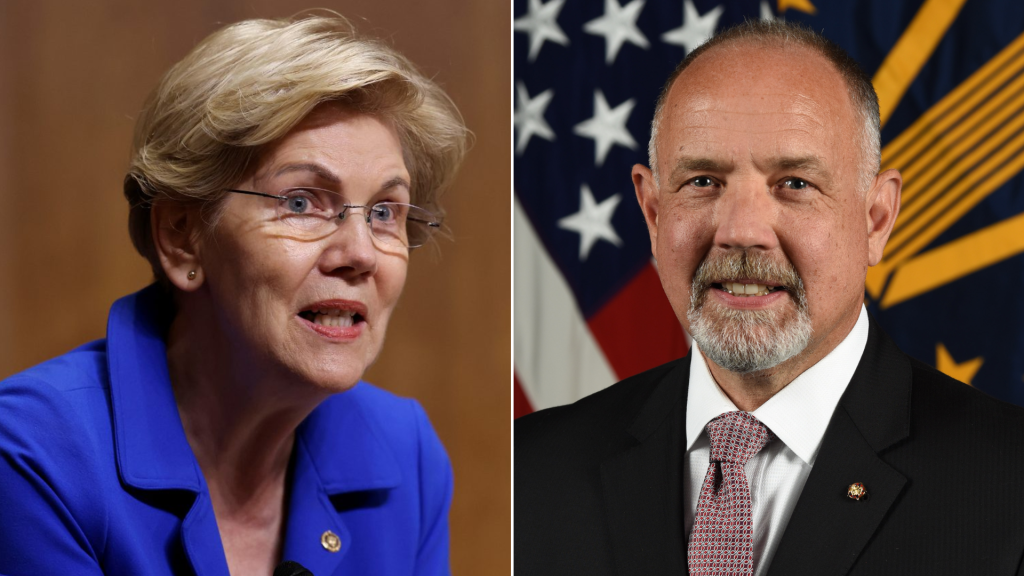

At the center of the confrontation was Charles Young, a longtime military lawyer and former acting general counsel at the Department of Defense. Warren pressed Young repeatedly on reports that Judge Advocate General (JAG) officers had been sidelined after raising concerns about the legality of recent deployments of National Guard troops and other military resources in support of immigration enforcement.

Her questions were sharp, insistent, and narrowly framed. If a military lawyer raises doubts about legality, Warren asked, is it appropriate to tell them to “shut up and get out of the way”?

Young declined to play along. Rather than offering the simple yes-or-no answer Warren demanded, he responded with a broader explanation of how the system is designed to function. Under military law, he said, JAG officers are empowered to provide independent legal advice to commanders and senior civilian leaders, and leadership is expected to listen carefully when those concerns are raised.

“I’m not aware of a response of that nature,” Young said, referring to the alleged silencing of legal officers.

The exchange quickly grew sharper. Warren cited reporting suggesting that a top uniformed Army lawyer had been dismissed after objecting to the legality of using Guard units for domestic enforcement. Young flatly denied telling any officer to stop “meddling,” arguing instead that the dispute had been mischaracterized and involved technical questions about whether state-controlled Guard personnel could be used in certain roles.

For Warren, the denial was not reassuring. She broadened her critique, pointing to other reported incidents in which military lawyers were allegedly overridden when questioning operations near Venezuela and the Caribbean, including controversial strikes on suspected drug-smuggling vessels. These deployments, she argued, were not only legally questionable but also extraordinarily costly, draining billions of dollars that could have gone toward military readiness, housing, and family support.

Young remained composed. Drawing on nearly three decades of experience as a judge advocate in multiple branches, he insisted that the military’s legal advisory system remains intact. JAG officers, he said, are able to communicate concerns “quickly and clearly” and do so independently.

“I don’t have concerns about the judge advocates,” Warren replied pointedly. “I have concerns about the leadership.”

That line captured the essence of the moment. This was not simply a disagreement over facts. It was a dispute over trust.

To Warren and her allies, the fear is that legal review is being treated as an obstacle rather than a safeguard — that lawyers who raise inconvenient questions risk being ignored or removed. In that view, sidelining JAG officers would undermine one of the military’s most important internal checks: the obligation to ensure orders are lawful before they are executed.

To Young and defenders of the current administration, the accusation itself reflects a different danger. They argue that legal scrutiny is being weaponized by Congress as a means of exerting political control over the executive branch, especially during moments of crisis or rapid decision-making. From this perspective, Warren’s insistence on forcing admissions is less about protecting the rule of law than about constraining presidential authority through legal pressure.

The clash also reflected a broader historical tension. Civilian oversight of the military is a cornerstone of American democracy, but that oversight has always been mediated through institutions, norms, and professional judgment. JAG officers occupy a unique position in that structure: they are both military officers and lawyers, bound by duty to the chain of command and to the law itself.

When those roles come into conflict, the system relies on trust — trust that legal advice will be heard, and trust that questioning legality is not an act of insubordination.

That trust is clearly fraying.

Warren framed the issue as one of accountability, warning that deployments without clear legal grounding erode morale and expose service members to moral and legal risk. She noted that during previous administrations, similar military support missions were curtailed precisely because of cost and demoralization.

Young countered not with confrontation, but with institutional confidence. He portrayed a system still functioning as designed, one in which legal concerns are raised and addressed, even if outsiders disagree with the outcomes.

The hearing ended without resolution. No smoking gun was produced, no admission secured. But the moment lingered.

What played out was less a personal defeat or victory than a signal of what lies ahead. As military operations increasingly intersect with domestic policy, immigration, and law enforcement, the legal gray zones will multiply. So will the pressure on lawyers, commanders, and lawmakers to define who gets the final word.

In that sense, the exchange was not about Elizabeth Warren losing her temper or a Pentagon lawyer stonewalling a senator. It was about a constitutional balancing act under strain — between law and power, advice and authority, and the enduring question of how a democracy restrains force without paralyzing it.