By XAMXAM

For years, the question surrounding the Epstein files has not been whether information exists, but whether it would ever be released in full. Deadlines came and went. Subpoenas were issued, challenged, delayed, and ultimately neutralized by time. Accountability did not collapse under scrutiny; it simply aged out of relevance.

That familiar pattern is now being tested in a way Washington has rarely seen.

As the statutory deadline mandated by the Epstein Files Transparency Act arrives, the Department of Justice faces a constraint it cannot maneuver around in the usual ways. This is not a subpoena that expires with a Congress. It is a law. And unlike most confrontations between Congress and the executive branch, this one was designed to survive delay itself.

The architecture of the law explains why this moment is different. Subpoenas rely on enforcement by the same institutions they seek to compel. They invite litigation, appeals, and procedural stalling. Eventually, a Congress ends, leadership changes, or political incentives shift. What remains unresolved quietly disappears.

The Transparency Act breaks that cycle by targeting not a person, but an office. The obligation does not belong to a particular attorney general; it belongs to the Department of Justice itself. Whoever occupies that role now or in the future inherits the same legal duty. Noncompliance does not reset with time. It accumulates.

That design choice transforms the deadline from a suggestion into a structural test. The question is no longer whether officials intend to cooperate, but whether the law itself has teeth when enforcement becomes uncomfortable.

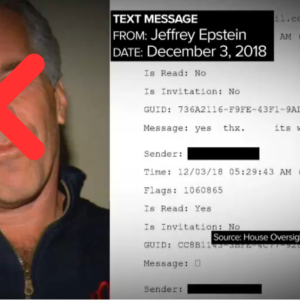

What sharpens the stakes further is the way the law allows the public to detect evasion. This is not a matter of trusting assurances that “everything has been produced.” Victims’ attorneys, investigators, and long-time observers of the case already know what categories of documents exist — particularly FBI FD-302 interview summaries that memorialize victim testimony. Those records are expected to contain names of alleged perpetrators beyond Jeffrey Epstein himself.

If the released materials contain no such names, the absence will be telling. Not because guilt is assumed, but because omission becomes measurable. Transparency, for once, can be audited.

That reality places prior sworn testimony under a harsher light. Public statements made in interviews are easily dismissed as political spin. Statements made under oath are not. FBI and DOJ officials have testified that no credible evidence exists implicating anyone beyond Epstein. Some acknowledged that they relied on staff summaries rather than personal review.

If forthcoming documents contradict those statements, the issue shifts decisively. It is no longer about interpretation or judgment calls. It becomes a question of accuracy under oath — a line institutions cannot cross casually without consequences.

Equally significant is the collapse of a long-standing justification for secrecy: grand jury rules. For years, courts cited those rules to block disclosure. After passage of the Transparency Act, multiple federal judges reversed course, ruling that the new statute overrides prior constraints while still requiring redaction of victim-identifying information. That ruling undercuts the claim that transparency and survivor protection are incompatible goals.

The law anticipated that argument and addressed it directly. Victims’ names are protected. Allegations are not erased.

Another familiar refuge — the “ongoing investigation” excuse — has also been narrowed. The statute allows limited, temporary redactions tied to specific investigative needs. It does not permit blanket withholding. Opening new investigations does not authorize the concealment of entire archives. The law was written to prevent precisely that maneuver.

Timing adds to the tension. Congress adjourns just as the deadline hits, creating a brief window in which compliance could be partial or late without immediate confrontation. That window, however, does not offer immunity. Because the obligation persists, any failure follows the office until corrected.

This is what makes the moment unusual. Accountability is no longer racing against the clock. The clock has been removed from the equation.

The broader implications extend beyond Epstein. This is a test of whether institutional power can still rely on complexity, delay, and public exhaustion to avoid reckoning. The law’s language is modern. Its requirements are explicit. Judges have already complied. The president signed it. Ambiguity is not the issue.

What remains is choice.

If the documents are released fully, the public gains clarity long denied. If they are not, the failure becomes traceable and durable, not fleeting. Either outcome establishes a precedent: that some deadlines matter not because of who demands them, but because of how they are written.

In Washington, accountability has often depended on urgency. This time, it depends on permanence. The Epstein files deadline does not ask whether officials are willing. It asks whether the rule of law can function when delay is no longer an option.

The answer will not be found in press statements or reassurances. It will be found in what appears — and what does not — when the files finally emerge.