“A Clear Conflict”: Sarah Jacobs Presses Marco Rubio on Trump’s Profits, UAE Arms Sales, and the War in Sudan

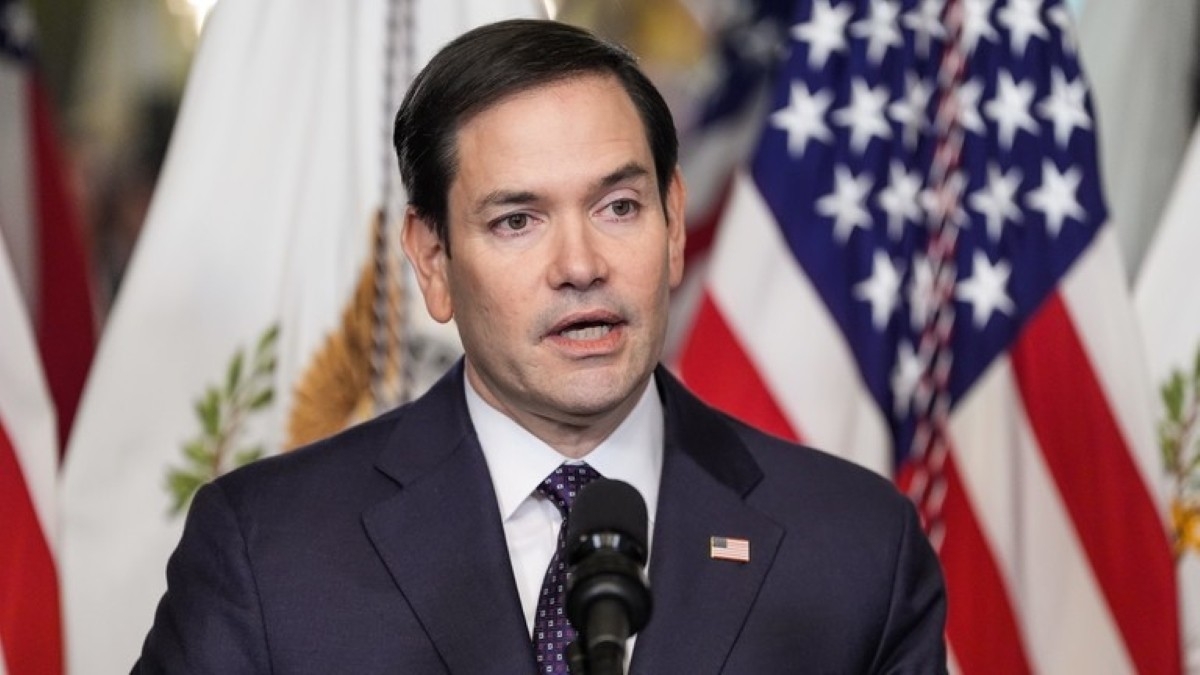

A tense exchange in a House hearing this week laid bare one of the most uncomfortable questions facing the Trump administration: can American foreign policy be trusted when the president is personally profiting from relationships with foreign governments receiving U.S. weapons? Representative Sarah Jacobs of California forced that question into the open during a pointed confrontation with Secretary of State Marco Rubio over U.S. arms sales to the United Arab Emirates amid an unfolding genocide in Sudan.

Jacobs began not with politics, but with the humanitarian reality. Sudan, she reminded the committee, is experiencing the world’s largest displacement crisis, with famine spreading and atrocities mounting. Having recently visited Sudanese refugees in Chad, she spoke of suffering she had witnessed firsthand. Rubio agreed with her core premise: the Rapid Support Forces, a militia operating in Sudan, are committing genocide, and the UAE is openly supporting them. That shared acknowledgment removed any ambiguity about the facts on the ground.

The dispute centered not on whether the UAE is a strategic partner — a point Jacobs explicitly conceded — but on the sequence of events leading up to a major U.S. weapons sale. On April 30, the Trump Organization announced plans to build an 80-story Trump Tower in Dubai. On May 1, World Liberty Financial, a cryptocurrency company owned in majority by Donald Trump and his family, secured a $2 billion deal with an Emirati firm closely tied to the government. Just 11 days later, the State Department notified Congress it would bypass a hold on more than $1 billion in arms sales to the UAE.

For Jacobs, the timeline was not incidental. It raised a direct ethical question: is it a conflict of interest for a president to personally profit from business deals with a foreign government while authorizing lethal weapons sales to that same government — one that is enabling genocide? She pressed Rubio repeatedly for a yes or no answer. He refused to give one.

Instead, Rubio argued that any U.S. president would have to deal with the UAE, citing its role in the Abraham Accords and its cooperation on regional security. Jacobs pushed back, noting that diplomacy is not the same as private enrichment. Engaging a foreign government as part of U.S. policy, she said, is fundamentally different from retaining ownership in companies that profit from that government’s state-backed deals.

When Rubio suggested that the president was not personally involved in those business transactions, Jacobs produced documentation showing that Trump and his family retain a 60 percent ownership stake in World Liberty Financial, with Trump himself serving as the face of the brand. The denial, she argued, did not withstand even basic scrutiny. Still, Rubio rejected the premise that personal benefit had anything to do with the administration’s decisions.

The moment crystallized what critics see as a broader pattern: ethical questions deflected through procedural arguments and loyalty to the president overriding long-held commitments to transparency and human rights. Jacobs accused Rubio — once a vocal advocate for democratic values — of prioritizing political favor over moral clarity. “Anyone with any common sense can see this is a conflict of interest,” she said, linking presidential profit directly to human suffering in Sudan.

That theme resurfaced moments later when another lawmaker posed a hypothetical: would it be outrageous for a secretary of state to accept a $200,000 Rolls-Royce from a foreign government? Rubio ultimately conceded that it would be unacceptable — a response that underscored the contradiction at the heart of the exchange. If lavish personal gifts from foreign governments are improper, critics argue, so too is private profit tied to foreign policy decisions.

Beyond the personalities involved, the exchange carried significant implications. Arms sales are not abstract transactions. They shape wars, empower actors on the ground, and carry moral and legal weight. When those decisions coincide with personal financial gain at the highest level of government, the credibility of American leadership is put at risk.

Jacobs’ questioning was not a rejection of diplomacy or pragmatism. It was a demand for ethical boundaries. The Constitution grants Congress the authority to oversee foreign policy precisely to prevent the entanglement of public power and private gain. Rubio’s refusal to acknowledge even the appearance of a conflict left that concern unresolved — and, for many watching, reinforced it.

In the end, the exchange revealed more than a policy disagreement. It exposed a fault line between governance and enrichment, between accountability and loyalty. Whether Congress will act on that divide remains uncertain. But the question Jacobs posed — simple, direct, and unanswered — now sits squarely in the public record.