Massie Warns DOJ: Failing to Release Epstein Files Is a Crime

WASHINGTON — With just days remaining before a statutory deadline, Representative Thomas Massie, Republican of Kentucky, has issued a stark warning to the Department of Justice: failure to release the long-awaited Epstein investigative files would not merely deepen political controversy, but could constitute a crime.

Mr. Massie, one of the architects of the Epstein Files Transparency Act, said in recent interviews that the law leaves little room for discretion. Once enacted by Congress and signed by the president, he argued, compliance became mandatory. “This isn’t about contempt of Congress or politics,” he said. “This is a new law, with criminal implications, if it’s ignored.”

The statute requires the Justice Department to release records related to its investigation of Jeffrey Epstein, the financier who died in federal custody in 2019 while awaiting trial on sex trafficking charges. The law allows for narrow redactions to protect victims’ identities, but otherwise mandates disclosure by a set deadline, now less than a week away.

In recent days, the department has taken steps that some lawmakers interpret as progress. Federal prosecutors asked three judges to reconsider earlier decisions sealing grand jury material connected to Epstein and his associate Ghislaine Maxwell. All three judges agreed, citing the new transparency law, and authorized the release of grand jury records to the Justice Department, with victim names redacted.

Mr. Massie called that development “encouraging,” but stressed that it represents only a fraction of what the law requires. “The grand jury material is just a small piece,” he said. “The FBI and DOJ likely possess evidence that never went to a grand jury at all.”

That distinction has become central to the debate. Grand juries, former prosecutors note, are shown only what investigators believe is necessary to secure an indictment. Sensitive, politically fraught or legally complex material is often left out and retained in investigative files, interview summaries, internal memoranda and evidence logs.

According to Mr. Massie, it is precisely that unreleased material that Congress sought to expose. “What the public wants to see,” he said, “are the facts and evidence that the FBI and DOJ have never given to a grand jury — especially material that might implicate people beyond Epstein and Maxwell.”

The Justice Department has not publicly detailed the full scope of records it intends to release, nor has it said whether it believes the disclosure of grand jury material alone would satisfy the law. Officials have cited longstanding concerns about privacy, victim protection and the integrity of past investigations.

But supporters of the statute argue that those concerns were addressed in the law itself. Courts routinely redact names, withhold images and shield identifying details, they note, without withholding entire categories of evidence. “Protecting victims and releasing records are not mutually exclusive,” Mr. Massie said.

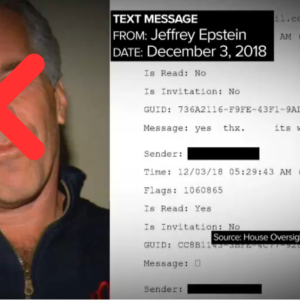

The dispute unfolds amid heightened scrutiny following the release of photographs from Epstein’s estate by Democrats on the House Oversight Committee. Those images, showing Epstein alongside prominent political and business figures, reignited public interest but offered little explanatory context. Lawmakers from both parties have said the photos underscore the need for fuller disclosure, not selective release.

Mr. Massie framed the current moment as a test not only of transparency, but of institutional accountability. “When the executive branch slow-walks or narrows a law passed by Congress,” he said, “it sets a dangerous precedent.”

Legal scholars say the stakes extend beyond the Epstein case. Transparency statutes are designed to constrain executive discretion precisely when disclosure is uncomfortable. If compliance becomes optional in practice, they warn, future administrations may feel emboldened to reinterpret or delay similar laws.

For survivors of Epstein’s abuse, the drawn-out process has been particularly painful. Many were promised accountability after years of sealed records and secret agreements. Each partial release, advocates say, risks appearing less like progress than avoidance.

The Justice Department’s move to seek unsealing of grand jury material suggests it knows how to act swiftly when it chooses to, Mr. Massie argued. “That undercuts the idea that their hands are tied,” he said. “If they can go to court for that, they can go to court for the rest.”

As the deadline approaches, pressure is mounting. If the department complies fully, it could bring long-sought clarity to one of the most disturbing criminal cases in recent memory. If it does not, Mr. Massie insists, the issue will shift decisively.

“At that point,” he said, “this stops being about Epstein and becomes about whether the rule of law applies to powerful institutions as much as it does to individuals.”

Whether the Justice Department meets the deadline may determine not only the fate of the files, but public confidence in the promise that transparency, once written into law, is not optional.