By XAMXAM

The latest disclosure of records tied to Jeffrey Epstein was meant to signal progress after years of delay and distrust. Instead, it has become another episode that reinforces a central and unresolved question of the Epstein saga: whether transparency is genuinely being pursued, or carefully managed.

Late this week, tens of thousands of documents connected to the Epstein investigation briefly appeared on the website of the Justice Department. Within hours, they disappeared. When some of the files later resurfaced, document identifiers had changed, and the department offered no immediate explanation for the removal or the reshuffling. In a case already defined by secrecy and institutional failure, the moment felt less like a breakthrough than a familiar stumble.

The documents were released under the Epstein Files Transparency Act, a law designed to force the federal government to disclose investigative materials, internal communications, and charging deliberations related to Epstein and his associates. Lawmakers who supported the statute argued that only full disclosure could restore public trust after decades of missed warnings, lenient treatment, and unanswered questions surrounding one of the most prolific sex traffickers in modern history.

Instead, critics say the Justice Department’s handling of the release has done the opposite.

Some of the newly posted materials referenced prominent public figures, including former presidents. Mentions alone do not establish wrongdoing, and legal experts have been careful to emphasize that point. Yet the way the records were released — briefly visible, then withdrawn, then altered in format — has fueled suspicion that information is being curated rather than simply published.

The controversy intensified when a handwritten letter attributed to Epstein appeared among the documents. The letter, addressed to Larry Nassar, the former U.S. gymnastics doctor convicted of sexually abusing hundreds of young athletes, contained disturbing language and referenced powerful figures. Although the existence of such correspondence had been reported previously through public records requests, this marked the first time the text itself surfaced in a document release.

That appearance was fleeting. The letter vanished along with other materials when the document batch was pulled from the Justice Department’s website. It later reappeared with different reference numbers, prompting questions about whether documents were being edited, reordered, or selectively displayed. The department has not publicly clarified whether the letter has been authenticated or why it was removed and reposted.

For survivors of Epstein’s abuse, the episode was deeply frustrating. Many have argued that institutions consistently protected themselves — and powerful individuals — at the expense of victims. In this release, they noted, some documents exposed identifying details about survivors while key investigative records, including FBI interview summaries and internal prosecutorial memoranda, remained withheld or heavily redacted.

That imbalance has become a focal point of criticism. Transparency advocates say that releasing survivor information without fully explaining investigative decisions risks retraumatizing victims while failing to answer the public’s most pressing questions: who knew what, when, and why certain cases were never pursued.

Lawmakers from both parties have echoed those concerns. Several have argued that the law was written specifically to prevent reputational harm from being used as a justification for secrecy. They maintain that internal deliberations, draft indictments, and witness interviews were meant to be disclosed precisely because those materials illuminate how decisions were made — and how power may have shaped outcomes.

The Justice Department, for its part, has defended redactions in past releases as necessary to protect privacy and due process. But the sudden disappearance of an entire document batch has complicated that defense. Even without evidence of intentional wrongdoing, the optics are damaging. In matters of institutional trust, perception often matters as much as fact.

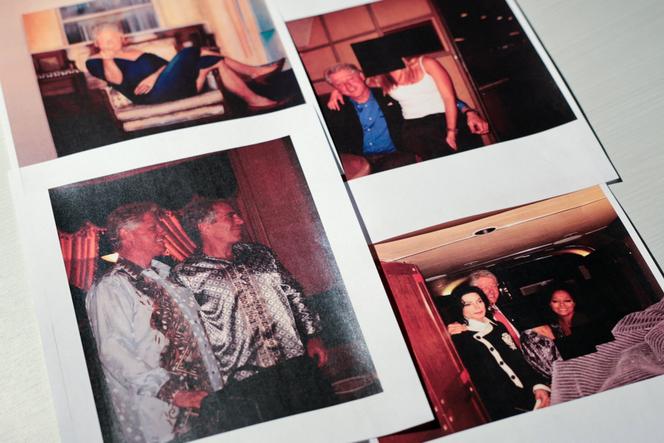

The contrast in responses from those mentioned in the files has also drawn attention. After photographs involving former President Bill Clinton circulated earlier in the release process, his representatives publicly called for the full publication of all Epstein-related documents, arguing that selective disclosure invites speculation and distrust. That stance has been repeatedly cited by critics questioning why similar clarity has not come from other quarters.

What makes this moment particularly significant is not the presence of any single allegation, but the cumulative effect of how information continues to surface. Each irregularity — a delayed release, a missing file, a changed document number — reinforces a belief that the Epstein case is still being handled differently from ordinary investigations.

For years, Epstein’s wealth and connections allowed him to evade consequences that would have been swift for less powerful defendants. His death in custody closed the door on a full criminal trial, leaving the public dependent on records and institutional honesty for answers. That places a heavy burden on the agencies responsible for releasing those records.

So far, the burden has not been met.

Rather than settling questions, the latest disclosure has reopened them. Why were the files removed? Who decided what to repost and how? And what remains unseen?

Until those questions are answered plainly, the Epstein files will continue to symbolize not closure, but a deeper failure — one in which transparency is promised, delayed, and delivered only in fragments.